Eric Henry Liddell (1902-1945) is best known as one of the heroes of the Oscar-winning film “Chariots of Fire”. The film focuses on his sporting achievements. But of greater importance was his “other life” as a missionary to China.

While at university in Edinburgh, Liddell played for Scotland’s national rugby team. In 1923 he shifted his focus to athletics. Liddell was selected for the British team for the 1924 Olympics in Paris and was a favourite for the 100 metres race. But because the heats were to take place on a Sunday, which Liddell believed was “the Lord’s day”, he refused to take part. His action brought him under enormous pressure from both the British Olympic team’s management and the popular press to compromise his faith. He refused to yield.

J. John explains why Liddell did that. “Liddell lived a life of surrender. He took the lordship of Christ seriously, and his breath-taking commitment stands as a rebuke against everything that risks taking the place of God in our lives, whether it be sport, pleasure or our careers. Whether we agree with Liddell’s attitude to sport on Sunday is irrelevant; it was a ruling that he believed God had laid upon him, and he refused to break it.” That is the point. Whether we agree with his “Sabbath” position or not, the principle is clear – the issue was surrender to the will of God.

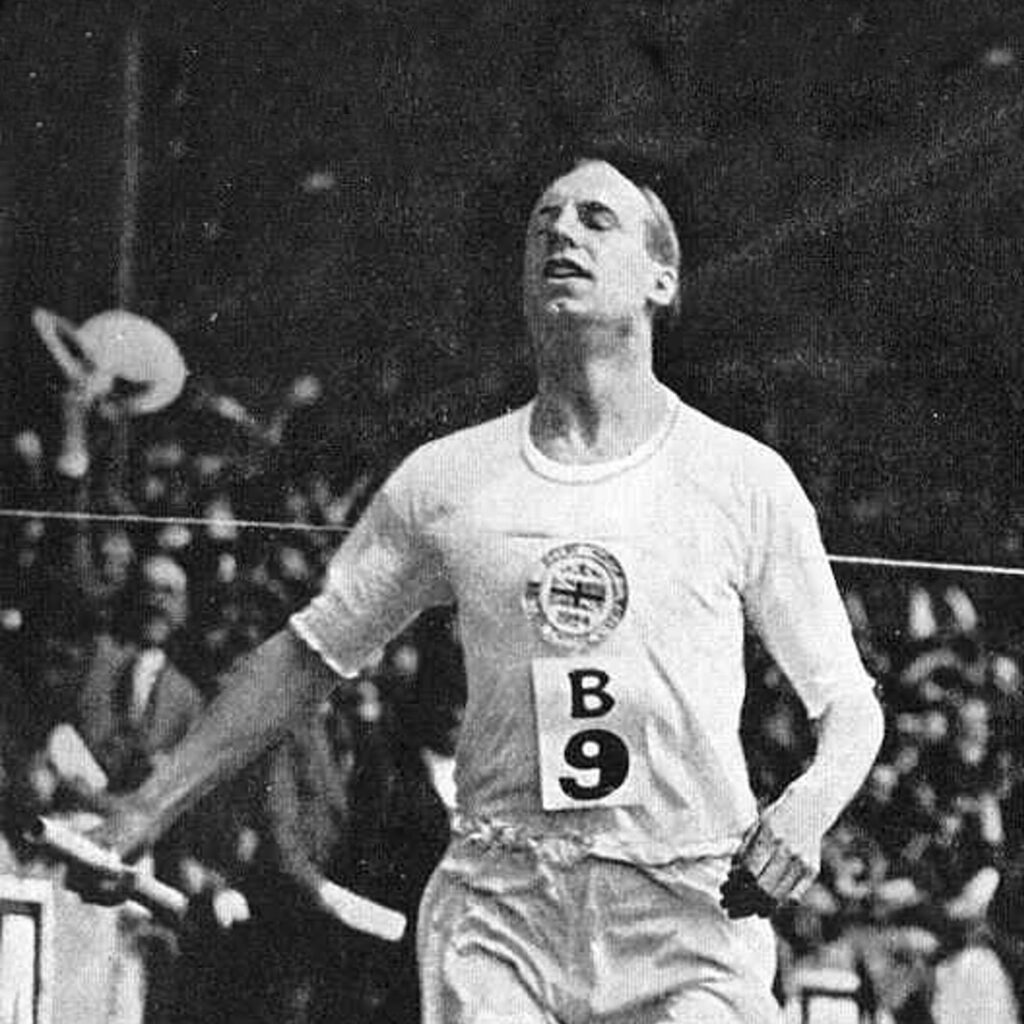

Liddell did, however, enter the 400 metres race, a distance over which he was not expected to do well. On the morning of the race, he was handed a paper which read, “In the old book it says, ‘He that honours Me, I will honour.’” Recognising the words from 1 Samuel 2:30, Liddell went on to run the race in an unorthodox way – and won a gold medal, breaking the Olympic and world records with a time of 47.6 seconds.

Liddell continued that life of surrender after the Olympics. Rejecting various appealing offers associated with sport, he expressed his firm belief that “God made him for China”. Liddell returned to Northern China to serve as a missionary from 1925 to 1943 – first in Tianjin (天津). He married Florence Mackenzie, whose parents were Canadian missionaries. The couple had three daughters, Patricia, Heather, and Maureen.

During the 1930s, a brutal three-way war between the Chinese Nationalists, the Communists and the invading Japanese made China perilous. Liddell went to serve in Xiaozhang (棗強縣) in Hebei province, with his brother, Rob, who was a doctor there. It was an extremely poor area that was severely short of help, and the missionaries there were exhausted. A constant stream of locals came at all hours for medical treatment. The town suffered during the civil wars and had become a particularly treacherous battleground because of the invading Japanese. By 1941 Japanese attacks meant that British nationals were advised to leave. Liddell said goodbye to his children and his wife, now pregnant with their third child. He did not see them again.

In 1943, he was interned at the Weihsien Internment Camp (濰縣集中營) in the modern city of Weifang, 濰坊, with many others. Liddell became a leader and organiser at the camp where food, medicine, and other supplies were scarce. Liddell busied himself by helping the elderly, teaching Bible classes at the camp school, arranging games, and teaching science to the children, who referred to him as Uncle Eric. However, he suffered an alarming decline in health in 1945 and, just five months before liberation, died from a brain tumour.

One of his fellow internees, Norman Cliff, described him as “the finest Christian gentleman it has been my pleasure to meet. In all the time in the camp, I never heard him say a bad word about anybody”. Langdon Gilkey said of Liddell: “Often in an evening I would see him bent over a chessboard or a model boat, or directing some sort of square dance – absorbed, weary and interested, pouring all of himself into this effort to capture the imagination of these trapped youths in the internment camp. He was overflowing with good humour and love for life and with enthusiasm and charm. It is rare indeed that a person has the good fortune to meet a saint, but he came as close to it as anyone I have ever known.” When Liddell died, Gilkey observed that “the entire camp, especially its youth, was stunned for days, so great was the vacuum that Eric’s death had left.”

He died as he had lived. Talking with a visitor to his sick bed, Liddell reached a point when he was unable to complete the word “surrender,” and instead he said “surren-…surren-“. With that he died. Eric Liddell passed into eternity as he had lived – surrendered to God’s calling for His life.