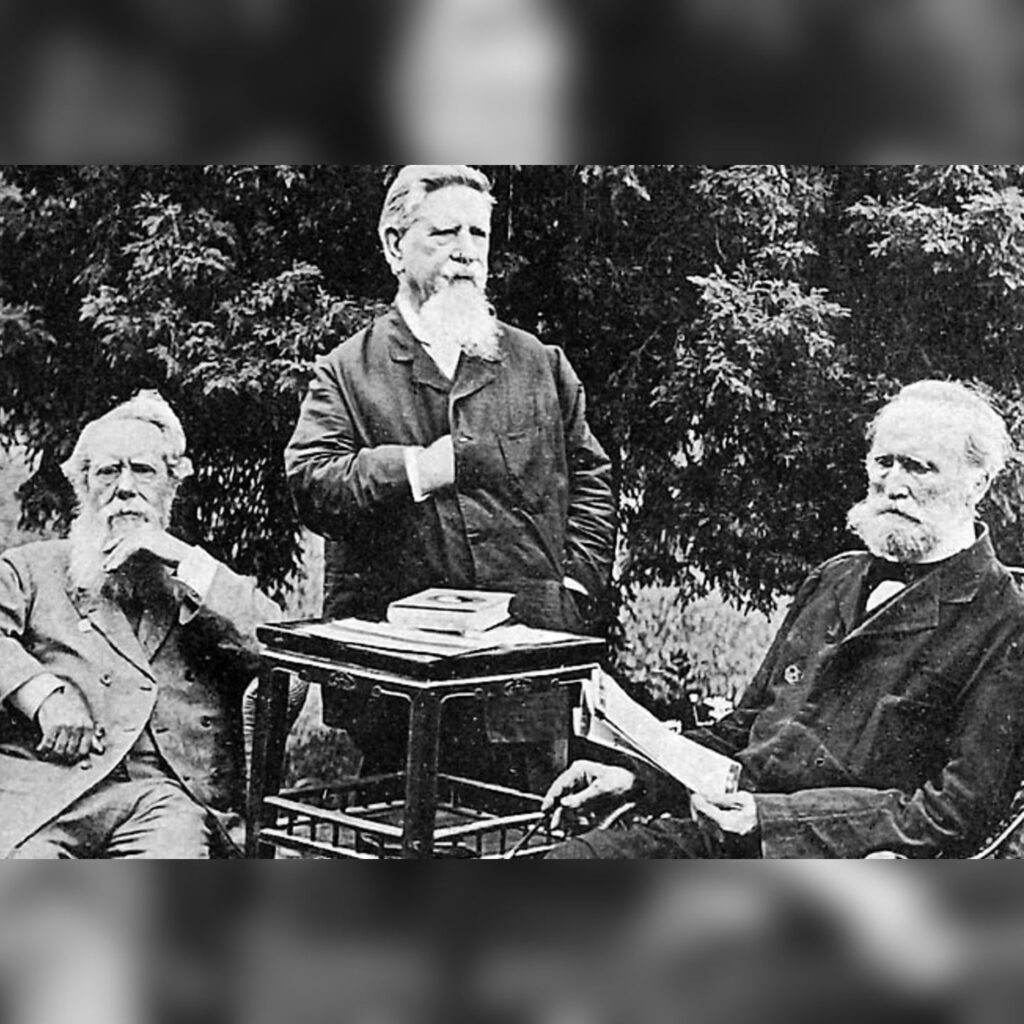

William A.P. Martin, 丁韪良 , (1827-1916), was an American missionary who served for 62 years in China between 1850 and 1916. The photo above, taken in 1905, shows three highly respected missionaries to China, whose mission approaches, at least as between Martin and the other two, were different and sometimes involved disagreements. Hudson Taylor (on the left in the photo) took the “Inland Mission” approach, that is, to reach Chinese all over China with the Gospel. Martin’s approach has been described as “top-down”, that is, through education and publishing “to win over Chinese intellectuals, change their worldview, and thus pave the way for the acceptance of the Gospel.”

As a young student, Martin had been profoundly influenced by Professor Andrew Wylie, who believed in “Manifest Destiny”, namely that “America’s mission was to bring ‘science, liberal principles in government, and the true religion to the peoples of Asia.’” That analysis explains Martin’s approach – the combining of education with evangelism, to introduce “Western values” – science, liberal principles in government as well as Christianity.

Ralph Covell argues that Martin was a ‘loner’ “with all the ambivalent characteristics of the pioneer… A man with boundless energy, a creative spirit, and iron will, and brilliant abilities as a teacher and writer.” Martin took diverging views on core issues for genuine reasons (to win Chinese intellectuals to Christ), but “when his ideas were resisted, he took positions designed to accentuate differences with his colleagues, and sometimes he deliberately provoked them.”

Regarding Confucianism, his position was: “There is no necessary conflict between Christ and Confucius.” He felt that Confucianism, “although correct and beautiful in his view, was not complete, for it had completely neglected the Divine dimension in doctrines of the ‘wu-lun’, the five human relationships.”

Regarding ancestor worship, Martin saw that it held a place of supreme importance for the Chinese. “Nothing has ever aroused such active Chinese opposition to Christianity as the discovery that it stands in irreconcilable antagonism to the worship of ancestors.” Martin thought that Christians should “prune off idolatrous elements and retain all that is good and beautiful in the institution.”

Somewhat ahead of his time (but in agreement with Hudson Taylor’s policy) he supported new moves for independence of Chinese churches from foreign control.

Martin was no ivory tower academic. He lived with his wife in the Chinese city of Ningbo. Martin said: “I wanted to be near the people…” He later criticised missionaries who stayed in their fortress-like compounds. Martin was soon engaged in preaching. He also engaged in itineration in the nearby area, “sometimes preaching to thousands of people at a time”.

While serving in Ningbo, he lectured on Christian apologetics. These lectures were later published in 1854 as T’ien-Tao Su-Yuan (Evidences of Christianity). Over the course of several decades, this book reached thousands of intellectuals, and, decades afterwards, was judged by his fellow missionaries as “the most popular Christian book ever published in China.”

He translated Henry Wheaton’s Elements of International Law. The book increased his stature and opened doors for future service in the government. Later, he was offered a job as “chair of International Law and Political Economy” at the T’ung Wen Kuan (“School of Combined Learning”), in 1869, he was invited to be president of the T’ung Wen Kuan, now given more prestige and support from the government. During his time at the school, Martin was involved in translating and producing nine books on science, international law, and political economy. As a reward for his faithful service, he was given the Mandarin rank of the third degree.

In 1898, he became the first President of Jingshi Daxuetang (Imperial University of Peking), China’s first modern national university and precursor of Beijing University. He was a significant figure in the last years of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Martin died of pneumonia in Beijing in December 1916. He was then the oldest foreigner in China, with the greatest number of years of continuous service. At his funeral, Li Yuan-Hung, president of the Republic, sent a statement saying that Martin “enjoyed an exceptional popularity as well as the respect of the scholars and officials both in the government and elsewhere in the country.”

All that Martin did during his six decades in China was aimed at winning the nation to the Christian faith. He perceived no conflict between direct proclamation of the gospel and secular education and reform efforts, since “he saw salvation as a coin with two sides – the material and the spiritual – but the spiritual was always the more important.”

Martin was faithful to his “top-down” vision, even if it differed from that of Hudson Taylor and others. One lesson we can learn from his life is our need to respect, but not necessarily to agree fully with, those whose vision differs from ours.

Source: Martha Stockment and G. Wright Doyle (Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity (BDCC).