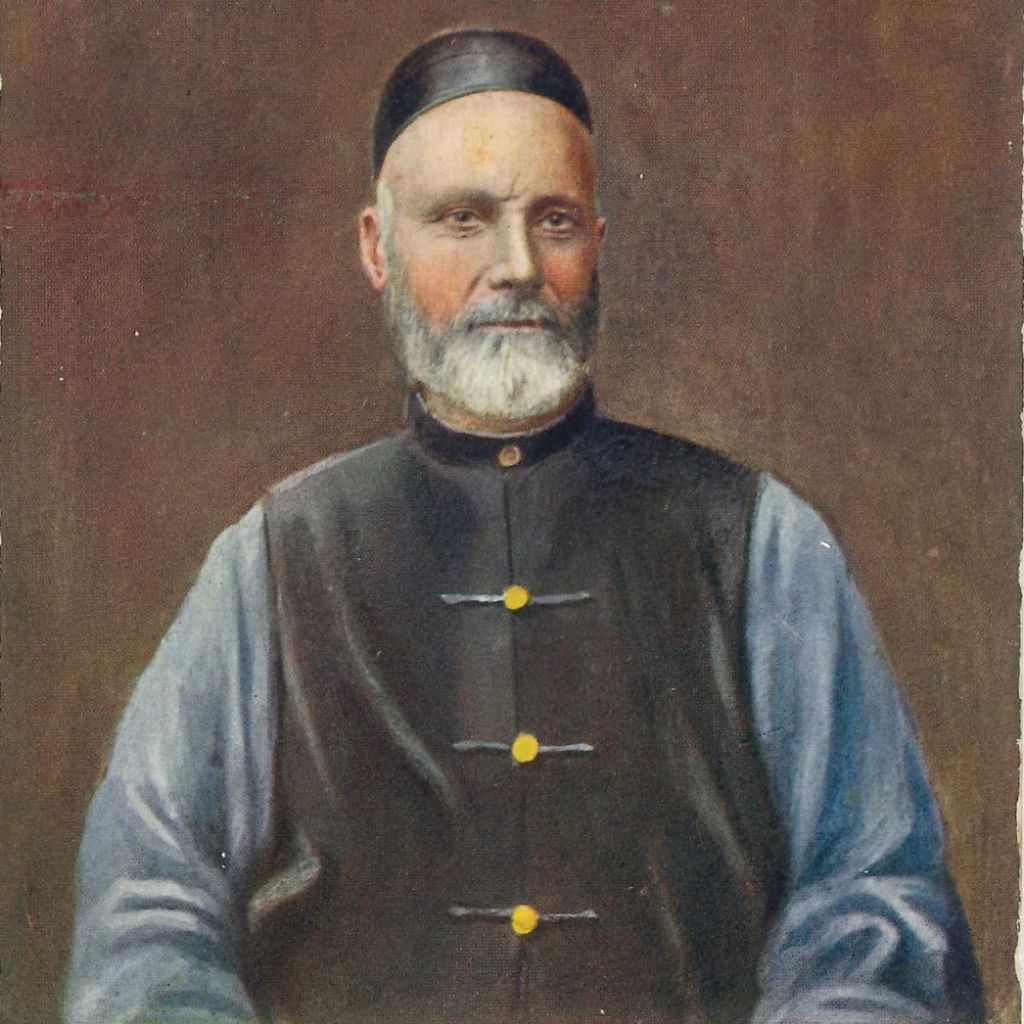

Having written recently about the lives of some of the New Testament colleagues of the apostle Paul, it’s easy to feel that these amazing cross-cultural workers were unique. But if we take another look at the lives of men and women like James Gilmour (景雅各, 1843-1891) it is clear that there are some more recent missionaries who can stand toe to toe with them.

James Gilmour was born at Cathkin, Scotland on 12 June 1843. The family was godly. “His mother delighted in gathering her sons about her in the evening and reading to them missionary stories and making comments upon them.” “Family worship was so strictly adhered to that neighbours would have to wait until the hour was passed before they could be served.” The family were comparatively well off. While he was a university student in Glasgow, James “furnished a small house which belonged to his father in the city.”

“James selected missionary service because the workers abroad were fewer than at home, and ‘to me the soul of an Indian seemed as precious as the soul of an Englishman, and the Gospel as much for the Chinese as the European.’ He had read the command in Matthew to ‘Go into all the word and preach’. He thought that there was a command to preach, but it was coupled with a command to ‘go into all the world’. He didn’t believe that what God had joined he could separate. He believed that God hadn’t called him to stay home, so if he were to be obedient he must go.”

He offered himself as a missionary to the London Missionary Society. They sent him for training in a college outside London. “On 10 February 1870 he was ordained as a missionary to Mongolia in Augustine Chapel, Edinburgh. He set sail from Liverpool, on 22 February 1870 on the steamship Diomed. He was made chaplain of the ship on which he sailed. At night he talked to every member of the crew while on watch, and laid the matter of salvation so clearly before them that he afterwards wrote, ‘All on board had repeated opportunities of hearing the Gospel as plainly as I could put it.’”

At the time Gilmour went to the field, “Mongolia embraced that vast territory between China proper and Siberia, stretching from the Sea of Japan on the east to Turkestan on the west, a distance of about 3,000 miles; and from Asiatic Russia on the north to the Great Wall of China on the south, a distance of about 900 miles.” In some areas there “were wandering tribes almost knowing no government or fearing no power. In the winter they lived in rude huts or tents; during the heated summers they sought the best pastures for their flocks… it was estimated that over half the male population were Buddhist lamas. To carry the Gospel to the nomadic bands of this land, Gilmour of necessity adopted a roving life and put up with its hardships.”

He set about learning Mongolian in the most unusual way. He came across a “Buddhist Mongol engaged in prayer. He arranged with this devout man, who had welcomed him, to share the hospitality of his home. The man lived alone, attended by two lamas that lived in adjoining huts. Here Gilmour spent three months, acquired the language rapidly and gained real insight into the hearts and minds of the natives.”

Gilmour’s work was hard. “At the end of 1874, after four years of labour, he could not report one convert, not even one who could be classed as interested in Christianity. The people did not have even a sense of need of what the Gospel was.” It was not until 1884 that he saw his first convert – “The place was as beautiful to me as the gate of heaven, and the words of the confession of Christ were as inspiring to me as if they had been spoken by an angel from out the cloud of glory.”

“Upon reaching a new city he pitched his tent on a main thoroughfare, and from early morn till late at night healed the sick, preached and talked to inquirers. During one eight months’ campaign he saw about 6,000 patients, preached to nearly 24,000 people, sold 3,000 books, distributed 4,500 tracts, travelled 1,860 miles and spent about $200, and only two individuals openly confessed to believe in Christ.”

In 1891 “suddenly he was stricken with typhus fever of a very malignant type. He died on 21 May 1891.” He was 47 years old.