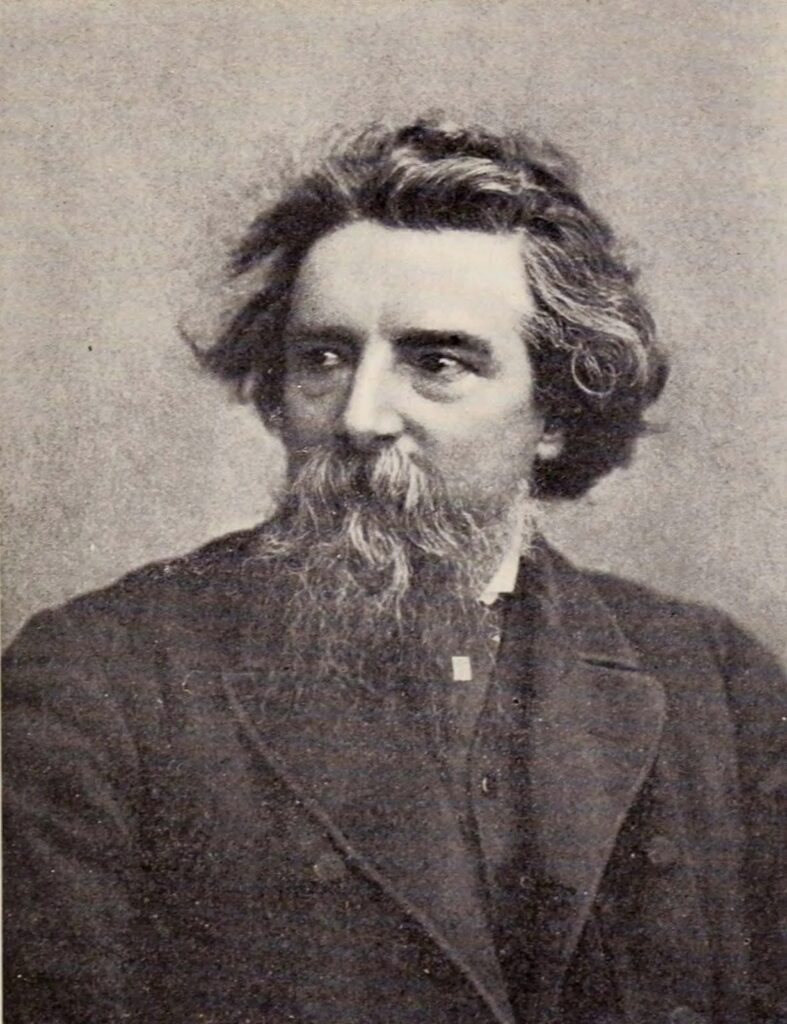

It was said of James Chalmers (1841-1901) that his fearlessness won the respect of the cannibals; his compassion, their loyalty and friendship. By the end of the 19th century, much of the New Guinea region had been reached with the Gospel through the faithful and sacrificial service of Chalmers and the many missionaries who proclaimed the gospel despite the constant threats of disease and death. Chalmers was characterised by a life of faith, prayer, love for the people, and a Christlikeness. He never doubted he had a gospel for the people.

As a young man Chalmers responded to a call to mission, and, on the advice of a missionary home on furlough, he applied to the London Missionary Society. James married Jane Hercus in October 1865. Their appointment was to Rarotonga, an island in the Cook group in the South Pacific. After a long delay, finally, on May 20, 1867, the Chalmers saw the mountains of Rarotonga. The first native they met wished to know his name. “Chalmers,” the missionary said. “Tamate,” was the nearest equivalent the man could call out to other Rarotongans, and Tamate became Chalmers’s name for the next 35 years.

For the next ten years, he was responsible for the smooth operation of an already-established mission. He reorganised an existing Training Institution and also set about educating native children. An important aspect of Chalmers’ missionary method was that he encouraged self-government and independence of European influence once a native work was well established. He wrote: “So long as the native churches have foreign pastors, so long will they remain weak and dependent.” He visited native churches on a regular basis and reported that the “out-stations under the charge of native pastors contrast very favourably with the stations under the care of European missionaries.” His philosophy was the same as that of the four men about whom I wrote recently who promoted the three-self principles.

But Chalmers was eager to pioneer a work for Christ, especially in New Guinea. In 1877 he finally received instructions to move there. New Guinea, or Papua, the largest island in the world, located across from the northern tip of Australia, was largely unexplored at the time of Chalmers’ arrival. “Several bands of native teachers from the islands went to New Guinea during that period, but only a few survived the ferocity of the cannibals and the trying climactic conditions.” He found the people “a very fine race physically, but living in the wildest barbarism. Tribal disputes were settled by bloodshed, and victorious tribes celebrated with cannibal feasts.”

For the next 23 years, he laboured up and down the coast, visiting 105 villages, 90 of which had never seen a white man, and establishing a chain of Polynesian teachers to continue the work. He always went unarmed, knowing this would allay native suspicions while leaving him defenseless in case of attack. He always preached Jesus.

Both the Chalmers worked tirelessly, he by conducting services and she by teaching. Those who accepted Christ were carefully nurtured in the faith. Chalmers only baptised those who demonstrated a genuine transformation and a growing knowledge of the Word of God.

Chalmers accomplished the seemingly impossible goal of promoting peace among the tribes all along the coast. A fellow missionary wrote: “Tamate’s power over the natives was partly a personal thing … It was in his presence, his carriage, his eye, his voice. There was something almost hypnotic about him … His judgment, largely the result of wide experience in critical situations, was unerring. He saw evil brooding where an inexperienced eye would have seen nothing to fear; he was equally certain everything was satisfactory, when a novice would have suspected danger. His fearlessness must have been a great factor of success in his hazardous work. He disarmed men by boldly going amongst them unarmed.”

The natives themselves testified most eloquently of his influence. When asked what prompted one tribe to give up cannibalism, an old chief said simply, “Tamate said, ‘You must give up man-eating’; and we did.”

For a long time, Chalmers had desired to make the dangerous trip to the Aird River Delta in order to win the people for Christ. He and his missionary colleague Oliver Tomkins waded ashore at Risk Point on Goaribari Island, New Guinea, on Easter Sunday, April 8, 1901. “Without warning, the natives attacked and dismembered their two visitors, passing the limbs to the women to be cooked, mixed with herbs.”

The news of Chalmers’s murder made headlines all over the world. Yet more than a century later most of us have never heard of him. That is one of the main reasons I write these columns – to bring to remembrance these heroes of the faith who paid such a high price to win the men and women who live “at the end of the earth” to faith in Jesus Christ.